ABB constructions in Chinese: collocate and ideophone

Shamelessly plugging my new article in Cognitive Linguistics, entitled “ABB, a salient prototype of collocate–ideophone constructions in Mandarin Chinese.” click me

ABB, not ABBA

Imagine.

The year is 2019. It’s September. You’re eating Chicago deep dish “pizza” in Taipei. Suddenly you hear people nearby play a fun game where they have to take turns saying a words of a certain form. If they’re too slow or say a wrong one, they’re out.

This actually happened to, and I couldn’t believe my ears. The words in question all had the syllabic template of ABB.

lǜ-yóuyóu

yìng-bāngbāng

hēi-xūxū

These, respectively, mean “very verdant green”, “super hard” and “deep black”. And as most speakers of Chinese languages will know, the BB part of them will add a certain vivid quality to the A part. The greenness of lǜ 綠 is elaborated in a vivid manner by the slipperiness of yóuyóu, which helps because yóuyóu 油油 means ‘oil oil’. On the other hand, the hardness of yìng 硬 ‘hard’ is elaborated by the hardness depicted by bāngbāng 邦邦. And the blackness of hēi 黑 by the BB part xūxū 魆魆.

These are one of the most fun parts of learning Chinese (honestly, all kinds of vivid words are fun to a certain degree, see Dingemanse & Thompson 2020) and absolutely necessary to become a fluent speaker of Mandarin, but also Cantonese or other varieties, and they have special predictive properties as well (see Thompson et al. 2022).

ABB, sound symbolism and ideophones

Already in the 1970s we find scholars like Benjamin K. T’sou (1978) stating that ABB forms are a particular locus for identifying sound symbolism in Chinese. Even if you don’t know what sound symbolism is, you may have hear about words like kiki and bouba. If I told you that one of these words sounds round and curvy, while the other is spiky and angular, there’s a very high chance that you would say kiki is the spiky angular one. There’s a whole field of linguistics that tries to identify patterns where the formal aspect of language (sound, but also writing) in some way reveal something about the meaning. That field is called iconicity.

Now, strictly speaking, not all statistical formal patterns that tell us something about the meaning are iconic, but that’s not the topic of this post. This post is also not about identifying particular mappings in ABB words.

What this post is about, is how ABB words - after that great observation by T’sou - were basically only studied from formal aspects and how they hang together with other permutations of patterns in which occur, think juggling letters like ABAB, ABB, BBA etc.

That led me to the belief (in my dissertation, Van Hoey 2020) that we should really be looking at these words from a more function point-of-view. If ABB words are so vivid, then that must mean there is at least the possibility that there is ideophony at play in them.

Ideophones can be cross-linguistically defined as “marked words that depict sensory imagery and which belong to an open lexical class” (Dingemanse 2019). But you probably know them as onomatopoeias. The only meaningful difference (for the majority of people in the field) is that onomatopoeia is seen as depiction of sound, while ideophones are much broader, covering senses like visual patterns, inner feelings, textures etc., which are not really in the scope of the term onomatopoeia.

Where am I going with this

Okay, so if ABB words potentially involve ideophone-like qualities, then most likely it will be in the BB part, as reduplication is a highly frequent trait of ideophones across languages. The A part, then, is somewhat of a fixed collocate of this ideophone. How do I know it’s fixed? Well, if you can play a game that’s not just random syllables of the form ABB, then there is a certain degree of idiomaticity at play as well.

So it stands to reason to think of ABB words as collocate-ideophone constructions.

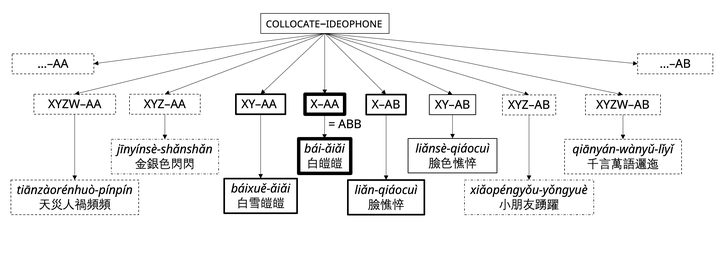

But ABB words are not the only party in town (a reviewer in my article that I’m gonna plug in a second did not like that phrasing so I’m recycling it here). There are many other collocates we can look at, in varying length.

In my article that recently came out in Cognitive Linguistics (currently ahead of print) I basically regale the story of ABB words, how they were studied traditionally, and what it would mean to treat them as collocate-ideophone constructions.

Of course, if they are collocate-ideophone constructions, they are probably “special” among those constructions, and I do find that they are prototypical in a sense. So finally I look at all the data from a number of perspectives, such as type frequency, token frequency, cue validity, dispersion. Finally, I put these single sources of information together in “tuples”.

Anyways, I hope you’ll check out the article.

Van Hoey, Thomas. 2023. ABB, a salient prototype of collocate–ideophone constructions in Mandarin Chinese. Cognitive Linguistics aop. https://doi.org/10.1515/cog-2022-0031.

And if you don’t have access to it, I’m more than happy to share it with you.

I don’t wanna read, I just want to hear your voice

Okay, for these people I also have a solution. I presented this in a talk last summer.

Van Hoey, Thomas. 2022. ABB, a salient prototype of collocate-ideophone constructions in Mandarin Chinese. In. Toronto; Nagoya: York University; Nagoya University.

You can find the talk on my YouTube channel, which I’m linking to here but also embedding below.